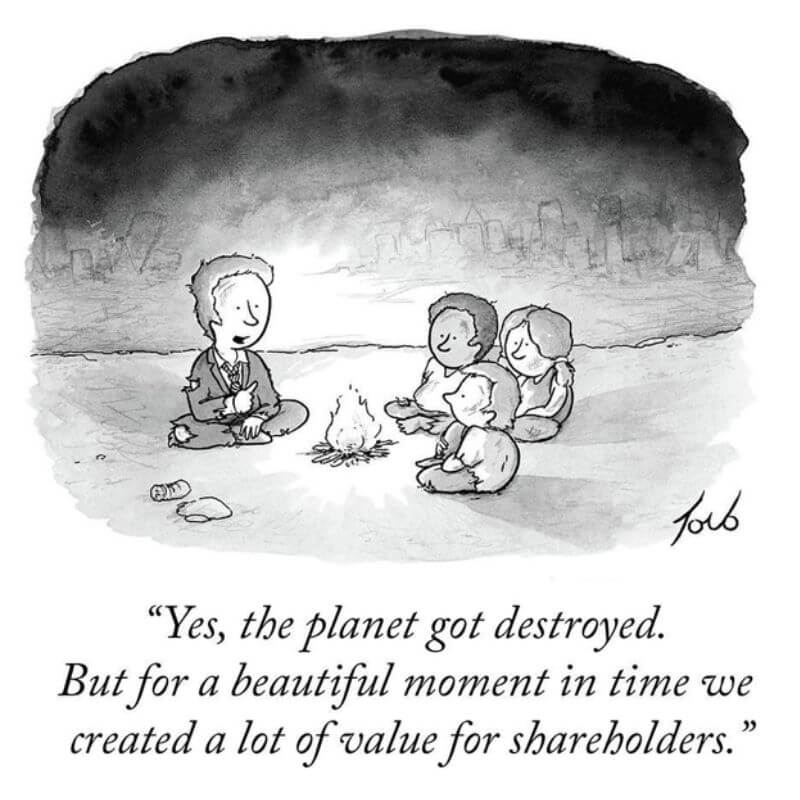

Despite the obvious absurdity of taxing our finite planet to infinity, growth remains the exclusive economic goal most officials in power cling to. What can explain their sobering lack of vision?

| This post belongs to a reading series of Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth. For quick access to all chapters, please click here. Disclaimer: This chapter summary is personal work and an invitation to read the book itself for a detailed view of all the author’s ideas. |

“The twentieth century bequeathed to us economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive, and we are now living through the social and ecological fallout of that inheritance. Twenty-first-century economists, especially those in today’s high-income countries, now face a challenge that their predecessors did not have to contemplate: to create economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow.” This, adds the author, calls for “transforming the financial, political and social structures that have made our economies and societies come to expect, demand and depend upon growth.”

Too Dangerous to Draw

GDP growth has been universally adopted as the de facto goal of economic policy, but “the textbooks never actually depict how it is expected to evolve over the long-term.” The tip of the GDP exponential growth curve is simply left suspended in mid-air, implying that it keeps rising indefinitely. As an example of what this means, let’s take a GDP growth rate of 3 percent on average worldwide.1 This equates to a doubling of the economic output every 23 years. Taking 2015, for instance, as a year of reference, the size of the economy is then supposed to become 10 times bigger in 2100 and almost 240 times in 2200! As Simon Kuznets, the father of GDP as a measurement tool, pointed out, “Objectives should be explicit: goals for ‘more’ growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”2 Though he was primarily speaking from a technical standpoint for the use of the GDP metric, his advice rings true when considering that we live on a finite planet. Instead of becoming knowledgeable about this required qualitative analysis, unfortunately, most policymakers prefer worshiping growth rather than questioning it.

Earlier economists had an intuitive understanding that the end of economic growth was inevitable. Adam Smith (1723-1790) envisioned a “stationary state” with its “full complement of riches” ultimately being determined by “the nature of its soil, climate and situation.”3 David Ricardo (1772-1823), says Kate Raworth, believed that “the stationary state would be brought about by the cost of rising rent and wages squeezing capitalists to the point of near-zero profits, and he feared it would happen soon (in the early nineteenth century) if technical progress and foreign trade could not keep it at bay.”4 John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) could hardly wait for what would be called today a post-growth society, saying “A stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as much room for improving the art of living, and much more likelihood of it being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by the art of getting on.”5 John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), later concurred, saying,”. . . the day is not far off when the economic problem will take the back seat where it belongs, and the arena of the heart and the head will be occupied or reoccupied by our real problems—the problems of life and of human relations, of creation and behaviour and religion.”6

In the grand scheme of things, all these authors’ interpretations about the economy’s future seem reasonable. Still, finance, business, and government are structured, says Kate Raworth, “to expect and depend upon a growing monetary income.” Effectively, “Financier only make a return—by extracting interest, rent or dividends—on economic value that has a market value. Business can only capture value as revenue and profit when that value has been monetized in sales. And governments find it far easier to levy taxes for public revenue on economic value that is exchanged through the market.” In other words, the economy is based on financial value. Money is not the mean but the end of trading in that scheme.

A different one could very well be implemented, where the economic value would be decoupled from the financial paradigm of debt creation and indefinite growth. There is indeed a distinction to be made between growth as measured by GDP and prosperity, and we have no choice but to make it since it is the only way to respect the environmental and social boundaries of economic sustainability. So, what are the alternatives to money as the economy’s main driver? This question can be answered by looking not only at the financial but also at the political and social levels of the world’s present addiction to growth.

Financially Addicted: What’s to Gain?

“The search for gains—which drives shareholder returns, speculative trading and interest-bearing loans—lodges dependency upon continual GDP growth deep within the financial system. For John Fullerton, the banker who walked away from Wall Street, here lies the source of the problem. ‘We’ve reached the logical conclusion of this expansionist economic paradigm,’ he says. ‘Unless we can achieve magical decoupling, we have an exponential function on a closed system planet… yet the finance system has no in-built plateau, it can’t “mature”—and none of the experts in finance are even thinking about this.'”7

That is why Fullerton and his colleague, Tim MacDonald, “started thinking about ways for regenerative enterprises to escape the pressure from shareholders to constantly grow. They came up with the concept of Evergreen Direct Investing (EDI), which delivers acceptable and resilient financial returns from mature low-or no-growth enterprises. Instead of paying profit-based dividends to shareholders, the enterprise pays out a share of its income stream to investors in perpetuity.8 This setup enables a profitable but non-growing business to attract stable investment from wealth stewards with a long-term view, such as pension funds.”

Aside from evergreen-type investments, another possible working angle to enact the difference between growth and prosperity is to change how money itself is used. Contrary to physical assets bound to deteriorate in time, money accumulates forever. What kind of currency could be aligned with the living world and promote regenerative investment rather than the prospect of endless accumulation?

One possibility, says the author, “is a currency bearing demurrage, a small fee incurred for holding money, so that it tends to lose rather than gain in value the longer it is held.” The idea was first laid out by Silvio Gessel, a German-Argentinian businessman, in his 1906 book titled The Natural Economic Order. According to him, only money that “goes out of date like a newspaper, rots like potatoes, rusts like iron” would be willingly handed over for objects that similarly decay. In other words, “. . . we must make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange.”9 Historically, adds Kate Raworth, “Paper-based demurrage was successfully used in city-scale complementary currencies in 1930s Germany and Austria to reinvigorate the local economy, and it was almost introduced across the United States in 1933. But in each case, the national government shut the initiative down, evidently threatened by its bottom-up success and the loss of state control over the power to create money.”

Demurrage money could boost regenerative investments, replacing the search for gain with maintaining value. Long-term regenerative goals such as reforestation could easily enter into that scheme.10 “Banks would consider lending to enterprises promising a near-zero return on investment if it were preferable to the cost of holding money: that would bode well for regenerative and distributive enterprises delivering social and natural wealth along with a modest financial return. And it would, crucially, help to release the economy from the expectation of endless accumulation and, hence, the financial addiction to growth.”

Demurrage is not that alien to today’s financial culture, as different countries’ negative interest rates used for emergency measures show. Even though technically challenging on many fronts—such as its implications for inflation, exchange rates, or capital flows—designing demurrage into currency is worth exploring for a financial world that would be in the service of thriving economies rather than supposedly ever-growing ones.

Politically Addicted: Hope, Fear and Power

The political world’s addiction to economic growth results from a psychological conditioning that includes three main aspects: “hope for raising revenue without raising taxes; fear of the unemployment line; and the power that resides in the G20 family photo.”

Hope for raising revenue without raising taxes

First, reframing the purpose of taxes would help build social consensus for the kind of higher-tax, higher-returns in the public sector that has been proven successful in Scandinavian countries. Words have a definite psychological weight in this regard. “Tax relief” sounds positive, but what about “tax justice”? Used by conservatives and neoliberals, the first slogan could be replaced by the latter, which is closer to the economic reality and would participate, incidentally, in preventing the economy itself from morphing into a play of Monopoly game. Or, by the same token, instead of referring to tax “spending,” why not say the real thing about the nature of taxes: “investment”?

Second, the injustice of tax loopholes, offshore havens, profit shifting, and special exemptions allowing the wealthiest people and the largest corporations in the world to pay negligible tax on their profits must be ended. “At least $18.5 trillion is hidden by wealthy individuals in tax havens worldwide, representing an annual loss of more than $156 billion in tax revenue, which could end income poverty twice over.11 At the same time, transnational corporations shift around $660 billion of their profits each year to near-zero tax jurisdictions such as the Netherlands, Ireland, Bermuda, and Luxembourg.”

Third, “shifting both personal and corporate taxation from taxing income streams and towards taxing accumulated wealth—such as real estate and financial assets—will diminish the role played by a growing GDP in ensuring sufficient tax revenue.” The idea, here again, is to decouple GDP—the blunt instrument exclusively measuring financial output—from economic wealth and prosperity.

Fear of the unemployment line

When the economy’s demand does not keep up with productivity growth, the result is widespread unemployment. “It was the Great Depression’s endless unemployment lines that convinced John Maynard Keynes to focus on full employment as the economy’s goal in the 1930s, and the answer, he believed, was continual GDP growth.” One of the main differences today with the 1930s, however, is that robots play an ever-increasing role in productivity, with the consequence that GDP growth cannot be considered anymore as equating with society’s economic health.

This constant shift upward in productivity ratio certainly reinforces the case of a basic universal income. Other solutions could also be worked out in a growth-agnostic economy, such as shortening the working week. This would imply getting rid of the current incentives in tax and insurance systems so that employers are encouraged rather than penalized for taking on more workers. The adaptation to fluctuating economic demand is even made easier when employers are the workers themselves. Reduced working hours are shared between all members in a cooperative. And finally, the widely recommended shift from taxing labor to taxing resource use “would simultaneously draw human ingenuity away from making more stuff with fewer people towards repairing and remaking more things with less stuff, while employing more people too.”

Power in the G20 family photo

“. . . keep growing to hold on to your spot in the family picture, or you’ll be bumped out of the frame by the next emerging powerhouse.” To the author, this incentive is “an international collective action conundrum and hence a tough growth addiction to tackle.” One way out of this bind would be to use alternative measures of success than GDP, reflecting human prosperity in a flourishing web of life. As Kate Raworth reminds us, “The UN’s Human Development Index, which ranks countries in terms of human health and education along with income per person, was created in 1990 precisely to start countering the sole use of GDP. Others, such as the Happy Planet Index, the Inclusive Wealth Index and the Social Progress Index, are now also aiming to create an alternative international family picture in which the biggest-GDP nations do not automatically appear centre frame.”

Another alternative to bypass the national GDP contest for the G20 family photo is to champion city-to-city collaboration. “The C40 network, for instance, now connects more than 80 of the world’s megacities in a shared commitment to tackle climate change. Home to over 550 million people and 25 percent of World GDP, these cities—and their economic vision—will be profoundly influential far beyond their city limits.”12

Socially Addicted: Something to Aspire To

“Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays realised that his uncle’s psychotherapy opened up a very lucrative world of retail therapy. His method of persuasion—tastefully named ‘public relations’—transformed marketing worldwide and, over the course of the twentieth century, embedded consumer culture as a way of life.” In the twenty-first century, moreover, online advertising “has taken personalised marketing into a far more sophisticated and invasive realm.” One way or another, as the media theorist John Berger already put it long ago, “publicity is not merely an assembly of competing messages: it is a language in itself which is always being used to make the same general proposal . . . it proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, and our lives, by buying something more.”13 According to Kate Raworth, consequently, “Reversing consumerism’s financial and cultural dominance in public and private life is set to be one of the twenty-first century’s most gripping psychological dramas.”

We are psychologically addicted to GDP growth for another reason as well. “When the economic pie is growing, the argument goes, the wealthy are more likely to accept redistributive taxes that invest in public services because it can be done without cutting into their take-home income. Others, however, believe continual GDP growth is essential for the very opposite reason: because it serves to permanently defer the need for redistribution. In the words of Henry Wallich, governor of the US Federal Reserve in the 1970s, ‘Growth is a substitute for equality of income. So long as there is growth there is hope, and that makes large income differentials tolerable’.”14

People need something to aspire to. But it is unlikely that it is simply consuming more. “Wherever and whenever we are excessive in our lives it is the sign of an as yet unknown deprivation,” argues the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips. “Our excesses are the best clue we have to our own poverty, and our best way of concealing it from ourselves.”15 The psychotherapist Sue Gerhardt concurs, “Although we have relative material abundance, we do not in fact have emotional abundance. Many people are deprived of what really matters.”16 Various studies show that just a few things promote well-being, notably: connecting with others, being physically active, taking notice of the world around us, learning new skills, and giving to others.17

***

[The book’s conclusion is titled “We Are All Economists Now.” Because it is quite short, the choice was made to have its summary here.]

“Ours is the first generation to deeply understand the damage we have been doing to our planetary household, and probably the last generation with the chance to do something transformative about it.” The task at hand is to figure out “the economics—and the philosophy and politics too—of the art of living in a distributive, regenerative, growth-agnostic Doughnut economy.” Of course, “Such an aspiration may seem foolish, even naive, given the intertwined crises of climate change, violent conflict, forced migration, widening inequalities, rising xenophobia and endemic financial instability that we face.” Notwithstanding, “As Donella Meadows made clear, the power of self-organisation—the ability of a system to add, change and evolve its own structure—is a high leverage point for whole system change. And that unleashes a revolutionary thought: it makes economists of us all. . . . from Bangla Pesa’s community traders in Kenya and Woelab’s recycled 3D printers in Togo to Newlight’s plastic-from-methane in California and the worldwide potential of peer-to-peer digital currencies, economic innovators are clearly succeeding in reshaping the economy’s evolution, making it distributive and regenerative, design by design.”

At a practical level, solutions will be worked on, tested, rejected, or adopted, as they have always been. At a moral level, a change of heart is required: we need the courage to believe in ourselves. And this is good news. If according to the best of science, the human species is objectively in the process of wiping itself out for good, answering a challenge of that magnitude is nothing complicated or far out of reach. It is simply time to find meaning first and act then, as opposed to what we are collectively used to doing. It is time for economics and politics to recognize our humanity as their primary guideline, both as the value that it is and the ultimate source of inspiration that it should be for all policymakers. A far cry from looking at growth as the “fairy dust that makes all the bad stuff go away,” as journalist George Monbiot put it in his presentation of Doughnut Economics.18

Share your thoughts below. Follow a gradual path with a Study Group.

Footnotes

- The average was 2.88 percent between 2017 and 2019, before the Covid 19 pandemic hit. See Macrotrends, World GDP Growth Rate 1961-2022.

- (Kuznets, S. (1962) How to judge quality, in Croly, H. (ed.), The New Republic, 147: 16, p. 29.)

- Smith, A. (1776) An Inquiry in the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book I, Chapter 9.

- See Economy and Taxation, Chapter 4 (6.29).

- Mill, J.S. (1848) Principles of Political Economy, Book IV, Chapter VI, 6.

- Keynes, J.M. (1945) First Annual Report of the Arts Council (1945-46). London: Arts Council.

- Can financial reform fight climate change? Interview on The Laura Flanders Show, 8 July 2012.

- See Capital Institute (2015) Evergreen Direct Investing: co-creating the regenerative economy.

- Gessel, S. (1906) The Natural Economic Order, p. 121.

- See Lietaer, B. (2001) The Future of Money.

- See Oxfam International, Tax on the “private” billions now stashed away in havens enough to end extreme world poverty twice over

- See https://www.c40.org/ On the whole discussion about GDP’s international prepotency, see Rogoff, K. (2012) Rethinking the growth imperative, Project Syndicate 2 January 2012.

- Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing.

- See Wallich, H. (1972) Zero growth, Newsweek 24 January 1972, p. 62.

- Phillips, A. (2009) Insatiable creatures, The Guardian 8 August 2009.

- Gerhardt, S. (2010) The Selfish Society: how we all forgot to love one another and made money instead.

- List established in Five Ways to Wellbeing: the evidence. London: New Economics Foundation. Aked, J. et al. (2008)

- Finally, a breakthrough alternative to growth economics – the doughnut, The Guardian, Wed. 12 Apr 2017.