Can growth be equated to progress? Data show that it is not GDP growth by itself that improves people’s lives but how money is distributed, notably through investing in public infrastructures.

| This post is part of a reading series on Less is More by Jason Hickel. To quickly access all chapters, open the book title tab on the Authors & Books page. Disclaimer: This chapter summary is personal work and an invitation to read the book itself for a detailed view of all the author’s ideas. |

It is generally assumed, says Jason Hickel, that “We need to keep growing in order to keep improving people’s lives. To abandon growth would be to abandon human progress itself,” adding that “It’s a powerful narrative, and it seems so obviously correct. People’s lives are clearly better now than they were in the past, and it seems reasonable to believe that we have growth to thank for that.” But empirical evidence shows that “It’s not growth itself that matters – what matters is how income is distributed, and the extent to which it is invested in public services.”

Where does progress come from?

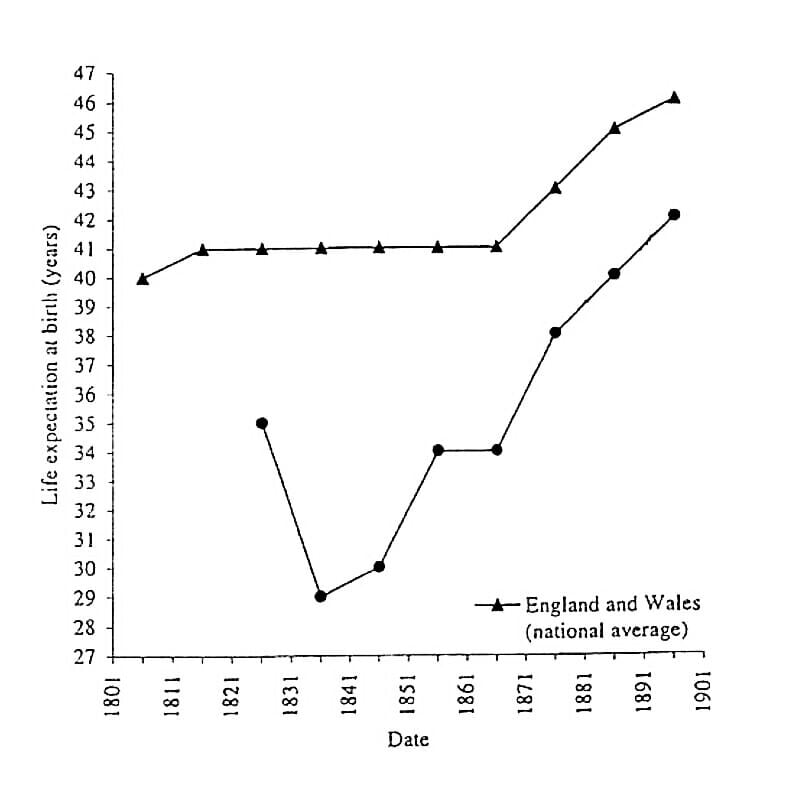

The fact, for instance, that populations in countries with higher GDP live on average longer than in poorer ones is often interpreted as proof that GDP growth equals progress. A closer look at history shows that extending life expectancy is primarily due to medical progress. In the second half of the nineteenth century, many people stopped dying at an early age once the importance of hygiene was scientifically established and public sanitation separating sewage from drinking water became a known necessity.1

The economic challenge for better personal and public hygiene was not in increasing national wealth but in the fact that “public plumbing requires public works, and public money. You have to appropriate private land for things like public water pumps and public baths. And you have to be able to dig on private property in order to connect tenements and factories to the system. This is where the problems began. For decades, progress towards the goal of public sanitation was opposed, not enabled, by the capitalist class. Libertarian-minded landowners refused to allow officials to use their property and refused to pay the taxes required to get it done.2

If nations with higher incomes tend to have better life expectancies, there appears to be no causal relationship between these two variables. Historical records show, on the contrary, that without progressive policies, growth has regularly worked against social progress, not for it. The resistance of elites in Western countries was regularly broken by social movements, strikes, and all forms of popular upheavals to eventually leverage the state’s power and obtain public healthcare, vaccination coverage, public education, housing, better wages, or safer working conditions. “And once you have these basic interventions in place,” says Jason Hickel, “the biggest single driver of continued improvements in life expectancy happens to be education – and particularly women’s education. The more you learn, the longer you live.”3