The United States is used to equating being “the greatest power in the world” and a democracy. But which is it? How and why a constitutionally limited government would turn into a superpower?

| This post is part of a reading series on Democracy Incorporated by Sheldon S. Wolin. To quickly access all chapters, open the book title tab on the Authors & Books page. Disclaimer: This chapter summary is personal work and an invitation to read the book itself for a detailed view of all the author’s ideas. |

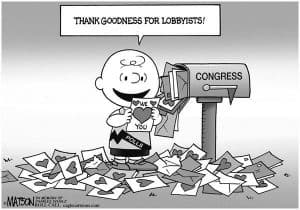

When George W. Bush said as a matter of pride that the United States is the “greatest power in the world” he was not necessarily doing the country a favor. Conflating power and greatness has never bode well for democracy, and the president himself proved it by opening an era of expanded executive powers concerning the right to war and against citizens’ privacy as well as public liberties. Defining a country by its power is, in any case, a particularly narrow path toward its greatness. This is in fact, as Sheldon Wolin points out, contradictory: “Does, or can, our Constitution, which typically has been understood as intending to limit power, actually authorize power of the magnitude being claimed by the president or is an extraconstitutional justification being claimed?” In other words, “How, and when, did the people delegate ‘the greatest power in the world’ to their government? If the people did not have that power in the first place, where does it come from?” There lies the perversion of democracy addressed in this chapter.

Contrary to classic forms of totalitarianism, the perversion of democracy does not announce itself in ways that could be immediately flagged as authoritarian. There is no dictator building power around his supposed charismatic persona, animated by the intent to become the center of gravity of all public institutions.1 As a matter of fact, inverted totalitarianism follows an entirely different course: “the leader is not the architect of the system but its product. George W. Bush no more created inverted totalitarianism than he piloted a plane onto the USS Abraham Lincoln. He is the pliant favored child of privilege, of corporate connections, a construct of public relations wizards and of party propagandists.” It follows that “Unlike the classic totalitarian regimes which lost no opportunity for dramatizing and insisting upon a radical transformation that virtually eradicated all traces of the previous system, inverted totalitarianism has emerged imperceptibly, unpremeditatedly, and in seeming unbroken continuity with the nation’s political traditions.”